What follows is a hunting story. I am relating it not because I am a Great White Hunter,

but because I am not. The following describes how I took my first deer. This was last December. I was already 27 years old. I thought of myself as a late-bloomer, making up for lost time. But I have come to learn that this is actually a very common predicament.

Here in America, we have a thoroughly industrialized culture. The average citizen has a very specialized field of expertise by which they make their living. And the consumer is usually very removed from their food source. But a good part of our national identity contains a certain notion of rugged independence; the cowboy, the homesteader, the long-hunter and the Native warrior are big parts of our cultural mythology. And while many of us (the real rednecks) are taught to hunt and take deer at age 12 or so, a good number of young Americans miss out on this experience and feel the want of it. I could go on about how this Wanting reflects some desire for a sense of agency, a search for authenticity, cultural alienation, spiritual longing, the ways of the fathers and so on. But it's not necessary to go into all that. The point is;

I am writing this for the benefit of the other late-bloomers.

I am also taking the advice of

Alexis Smolensk, who suggested that the best way to convey knowledge through D&D is to make a story of it.

So practically speaking, when a player says they want to go hunting for game, you can go "Ah-ha! That may not be so easy as rolling for success!" Just don't sound so menacing about it when you address the prospective hunter or she might change her mind and just scratch a ration off her sheet.

Hunting is a Rigmarole

Going on a hunt in the State of Oklahoma is an ordeal. Going through all the legitimate channels, the training, the paperwork and taxes involved are an initial test of the hunter's resolve. I blame the Normans. They started it all with their infamous forestry laws.

Early Conservationists

In a perfect world with perfect people, a citizen would be able to saunter into a public wilderness and take game. But there is good reason for these laws: it's all about conservation and safety. Hunters in Oklahoma are required to

take a hunter's safety course, and when applying for a license, they must show the card which proves they have received the education. This is very important. Even with this moderating effort, hunting on public lands is inherently dangerous. You must wear safety orange in hopes of keeping drunk, stupid rednecks from mistaking you for a white-tail deer. For this reason, it is

always preferable to hunt on private land.

Taxes and fees go to conservation and ecological monitoring. Natives and military veterans get off cheap. I'm not sure what exactly the dispensations for Natives really are. But the prevailing sentiment is that Natives are owed broad privilege in this matter.

Before hunting for deer, you must buy a tag for it, specifying whether you are targeting a buck or a doe. After your successful deer hunt, you are required to

register your kill, using the tag number. To do this, you pretty much need an internet connection. you will be asked to enter such details as the sex of you deer, the number of points on its rack (antlers,) the time of the kill, and the location. This information is useful to conservation-scientists.

You will then be permitted to print your tag. If you lack the wherewithal to do the skinning and butchering yourself, you can take your deer to a

processor who will charge a reasonable fee; such that even with taxes and fees, it still winds up as an economical way to get meat. The processor will need to see the tag to ensure that the game was taken legally.

Seasons are Enforced.

"If you aren't cold and/or wet, you're not hunting." so said my father. Some would call this an unnecessary purist attitude. But I have found it to be largely true. And this is Oklahoma , so the alternative is blazing heat.

Seasons are set as they are for conservation purposes. By the time it gets to deer season, the weather will likely have started to turn bitter. Dealing with the discomfort is part of respecting the animal and the process. Or so I tell myself. I have gotten to think that

hunting is an exercise in self-discipline.

The Outing

A guy at work invited me to come hunting with him. I guess I impressed him with my D&D stories. No shit. I was eager for mentorship, being aware that this is

not the short of thing you can learn from youtube videos. On Friday the 5th of December, we rode to a property near Chandler, OK. It was an 80 acre spread of mixed wood and field with a few cattle pens, owned by relatives of my guide.

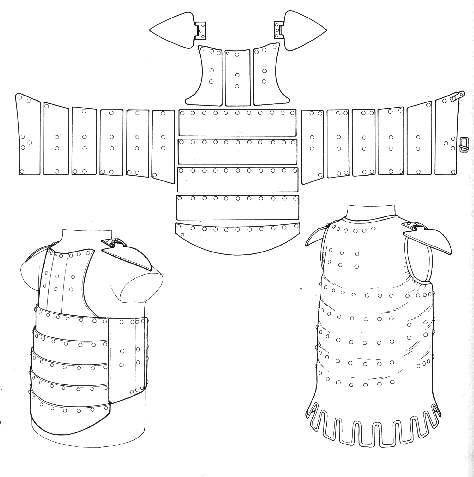

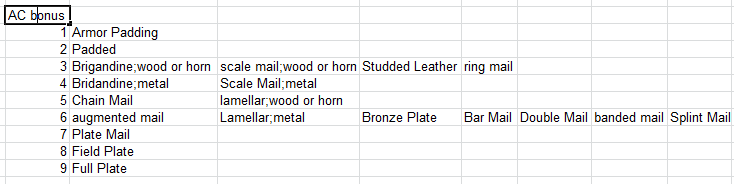

We arrived perhaps an hour before dark and put on our gear. I was expecting cold so I had a surplus M60 jacket over layers of long sleeved shirt. I wore black track pants over long johns (thermal underwear). This may seem counterintuitive, but I had learned this style from a backpacking excursion back in college. The synthetic outer layer helps to repel moisture and wind, while the cotton-blend inner layer maintains heat and wicks moisture. (The medieval equivalent of this would be wearing wool over linen.) I brought my military surplus Swedish Mauser Carbine. The Swedish Mauser is a bolt-action rifle which takes a 6.5x55mm cartridge, popular in Europe for big game hunting, but a little unusual in America. It has no scope mounts, but features an iron-sight which is adjustable for elevation to about 600 yards.

I left the bayonet at home.

I discovered that while my armament has notable historic value, it is not ideal for sporting. My guide had a Ruger bolt-action rifle chambered in .270 caliber. .270 is a popular sporting round in America, notable for its high velocity and relatively flat trajectory as compared to other full-sized rifle rounds. This weapon was notably lighter, was equipped with a fine Leupold scope, and had a much quieter safety-switch (important) My guide wore insulated overalls and a hunter-orange coat with a pattern of denuded branches to break up the silhouette.

He quickly smoked a cigarette, and when he was finished, he squeezed the ember out onto the ground, rather than simply dropping the cigarette and stepping on it, so as to track less of the distinctive smell into the woods with us.

It was about an hour to sundown. Deer tend to move at twilight; when they can still see, but have some measure of cover-of-darkness. It is also illegal to take deer after sundown or before sunup. We moved quietly perhaps a third of a mile to a blind which overlooked a swath of meadow which separated three stands of woods. Our blind consisted of a hay bale to sit on, with two hay bales stacked in from to provide concealment and a stable platform to shoot from. This whole arrangement was tucked under the eaves of two moist, dripping juniper trees. I was surprised at how

cushy the station was. The owner of the property had noted the advantage of this point, and constructed this relatively comfortable semi-permanent blind. He said that more deer have been taken that point than anywhere else on the property.

We sat very still, and kept very quiet.

I immediately noticed that sitting very still was a discipline which I had never had to practice before in my life. My guide whispered that the deer would come from where they bedded down, come from our right, and cross the meadow on their way to their watering hole, somewhere in the woods to our left. We waited. When twilight deepened and no deer came, my guide suggested that the deer were taking their time because of the full moon. With a full moon for light, deer do not restrict themselves to moving at twilight, but move more freely throughout the night. I felt myself growing cold, but tolerably so. It became too dark to aim reliably, and we left the blind. We went to the ranch-house, where I was introduced to our host; a well-to-do Fox-news devotee.

The White Tailed Deer and its Capabilities.

There are three species of deer in North America. The Mule Deer is the largest. Named for its large, mule-like ears, its range centers on the Rocky Mountain range. Mulies can be identified by the dark hair on the tops of their heads and stetching down the tail. Their antlers branch in a Y on Y pattern. Black-tailed deer are relatively small and have a rather narrow range in the Pacific Northwest. The most common and adaptable deer in America is the White Tail. Its range covers the temperate zones of practically the whole continent. The white-tail's antlers grow as single-pointed branches from a main beam which curves up-and-forward from the base

A deer has many abilities which make it a survival machine.

Despite their size, they are remarkably good at staying hidden in wooded environments. Their coloration and ability to stay very, very still makes them difficult to spot. One has to learn to look not for large, obvious deer silhouettes, but rather, to recognize parts of the deer under various lighting and shadows. When walking, they do so with a sinuous motion which seems to conceal their outline and does not draw attention with jerky movements. They can run faster than any human and easily clear most obstacles. Once a deer takes off, it is not worth wasting a shot unless you are an uncannily good marksman, and even then I wouldn't suggest it.

Deer are widely believed to be colorblind. But they can see with greater acuity, and better in dim light than a human. Their eyes are mounted on the sides of their heads, granting them a very wide field of vision. They are always paying attention.

Their hearing is especially keen. They can angle their ears like a dog or cat to better pick up on their surroundings. The ears can be rather expressive and their movement can give away a deer which is otherwise perfectly still otherwise. If deer hear something as subtle as rustling of clothing, rattling of arrows or the clicking of a rifle's safety, they are unlikely to stick around.

Last weekend though, I was noisily running up a flinty, wooded hillside, looking for my stupid dog when a white-tail erupted from the brush perhaps 25 yards in front of me and leapt away through the woods. When they are bounding about, they have abandoned stealth and their hooves make quite a loud thumping. It seems that if a deer hears something which is just stupid-noisy for a forest, they may stick around a moment out of sheer astonishment. It's the little stuff that spooks them right off.

I have also read and heard that while deer flee from humans, they are not nearly as alarmed by a man on a horse. They don't seem to recognize the outline as human, and are more likely to sit still.

A deer has an uncanny sense of smell. A white-tail has about 25% more olfactory receptors than a German Shepherd. So I read in Field and Stream. They of course know what a human smells like. Try to avoid perfume, gasoline, tobacco smoke, cooking meat, woodsmoke or body odour on your way into the hunting grounds. Even the perfumes in common detergents are enough to alert a deer. Washing your clothes in baking soda is a tried and trusted method of removing excess odours from your clothing. Remember the direction of the wind and try to stay downwind or at least crosswind of where you think the game is. There are several scent-based deer attractants on the market. Doe estrus urine is popular for attracting bucks, but has been known to work too well.

A deer is most likely to flee from a human, but is still wild animal and entirely capable of killing you. And nature has not equipped it to kill in a clean or quick manner.

by the genius Brad Neely

The above image- of a bleached skeleton in a rack is unlikely to occur however. Deer shed and regrow their antlers on a yearly basis- not long enough for a skeleton to bare itself. Antlers are shed in late winter or early spring and begin to regrow shortly after. By midsummer, the regrowth is complete and they begin to mineralize. By late summer, the antlers are fully calcified into an amazingly hard, durable material. This is just in time for mating season, when antlers are used by buck for dueling over reproductive privileges. Only bucks grow antlers.

Deer are herd animals. Females and fawns tend to move in groups and bed down in secure parts of the woods. They seek cover in thick brush, thorn patches and dense, scrubby woods. When browsing, they tend to scatter and spread out. They are creatures of habit and tend to use established networks of deer trails. They know when hunting season is and when they need to be especially wary. During these times, they avoid open areas or at least stick to the margins of the woods. when it is not hunting season, deer are more likely to act like punks. Bucks are more independent and range farther from main groups.

Clumps of glossy, bead-like pellets

Take This All Together, and now you have to shoot it.

And keep in mind our hunting strategy on this trip; to spot and shoot a dear from a long distance. This is the easy way to do it. It is baby-level hunting. It is made possible by modern firearms and optics for aiming them. To hunt with most any pre-modern weapon, one needs to be within 40 yards of the target, if not closer. Most hunters using modern compound bows consider 20 to 30 yards to be a fair distance for a reasonably accurate, ethical shot. This also depends on the deer presenting a good angle and standing reasonably still. Bow hunting is considerably more challenging, and this is why the bow season is much longer than gun season.

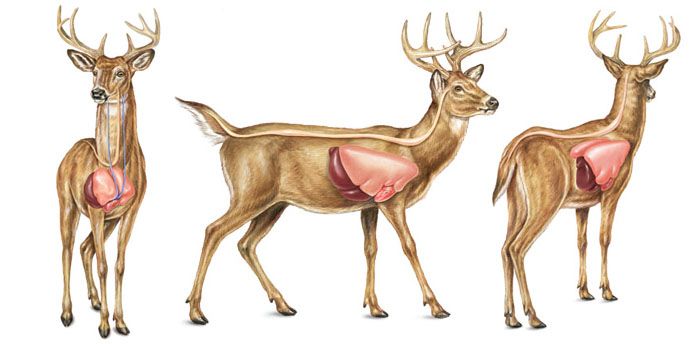

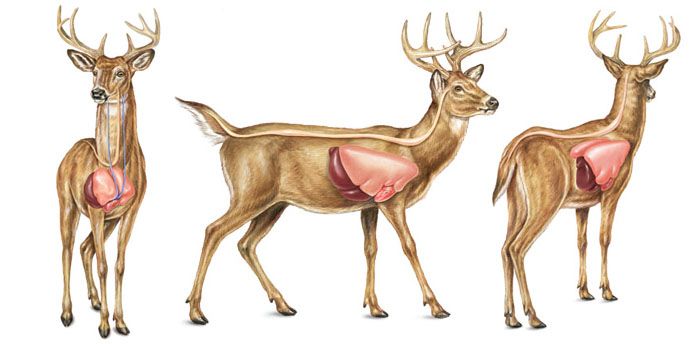

When an opportunity to shoot presents itself, the hunter much determine if the shot is worth taking. Ideally, a hunter will only take a sure shot which will kill the animal quickly and cleanly. If this is not possible, it is best not to take the shot. A rifle tends to kill quickly; the shockwave of the passing bullet creates a voluminous wound-cavity which pulps tissue and organs. But when hunting with a bow and arrow, a precise shot to a vital area is even more critical. An arrow typically kills by blood-loss, and it may be necessary to track the animal a ways to where it finally drops. I understand that when a stricken animal begins to run, it is best to not chase after immediately. Chasing right away will give the animal more motivation to run farther, and a better idea of where to run to get away from you. By widening the gap between itself and you, it makes it possible that you will just lose the animal.

To get close enough for a shot like this, one must pick a position where deer are expected to pass by; such as a blind, a tree stand or some other form of serious concealment, and Wait. Being very still and very quiet. This is a skill which takes practice, discipline and self control.

In D&D terms, wisdom should not be a hunter's dump stat.

The other option is to stalk the game; to literally sneak up on it. People do it. But I can't say how.

Teamwork and tactics can be a huge aid to hunting. One person may serve as a distraction or serve to spook the game towards where the other lies in wait. Or two hunters, stalking in a coordinated manner may be slightly more assured that the deer are not dodging them entirely. Possibly. Deer are slippery.

"Hunting," not "Killing."

The next day, in the pre-dawn, we crept past the cattle gates and into the woods. We found a tree-stand and mounted up, pulling our guns up on a line after us. The stand was perhaps 10 feet up and overlooked a gravel path which stretched toward the stand, then away at a right-ish angle. scrubby oak woods- slow passage for a human- lined the path. For hours, we waited.

Over the rest of the day, we stalked to another treestand at a higher elevation, from which we could see broad expanses of meadow. We sat tight for hours, into the afternoon without sight of any deer.

We trekked over to where they bedded down. This was distinguished by the amount of nearby scat. We saw nothing. My knife wandered off though. It was a

Mora, so I wasn't too heartbroken. Moras are great utilitarian knives and very economical. As twilight came on, I grew cold. My gloves and mask were thin and uninsulated. I also determined to acquire overalls like my guide had. I have also since determined to have a scope mounted on the Mauser. We did not spot a deer all day.

How to See

Sunday morning was our last shot at this. We returned to the blind beneath the junipers. It was a rather misty morning and very gray and dim. My guide seemed to have given up some of his optimism and ventured to converse- whispering more loudly than we had been wont to do. His conversation turned to the advice which only someone who has been divorced and remarried will offer a young man. A pinkish twilight started to grow and it became light. I took this as a bad sign, and said I would not mind if we called it a day.

But we sat a little longer. And my guide spotted something and pointed.

It took me perhaps six seconds to actually see what he saw.

200 yards away, down a hill, blurred by the haze, I could see a quadruped coming slowly in our direction. It had come from around a line of trees and was moving along the edge of the meadow, rather close to the trees. Its shape was vague, and it walked with a subtle, undulating motion which I did not yet know as that of a deer. The quality of the motion was not the sort of thing which would catch the eye unless one were looking very closely.

A human can only focus with optimal clarity upon an area about the size of one's thumbnail, held at arms length. Anything outside of that area is not in best focus. and even focusing upon the animal from about 200 yard, it still appeared as a gray blur upon a gray field. I could make out a long body and what looked like short legs. My guide and I thought it might be a coyote. Coyotes are fair game and I was far from above taking a coyote as a consolation prize.

My guide offered to let me use his scoped Ruger, I quickly and quietly took it, knowing that there was no way I would be able to aim effectively using my Mauser's dingey iron-sights. Looking through the scope, I saw that it was no coyote. There was the tracery of antlers, and the rest of the length of the slender legs appeared.

Through the scope, in the dim light, it looked like a ghost or a silent figment. My point is that to spot wild game takes a different sort of looking and seeing from that used for more mundane things, and this seeing is a skill which takes practice to learn.

Deer are strange and powerful.

It had turned and was offering a broad-side target. I was settling and focusing my aim, when my guide warned that it was about to disappear behind a brush pile. With my left eye, I was able to see what he meant, and I only had a few seconds left to shoot. My guide had mentioned that his scope was set to hit right on the cross-hairs at 200 yards, so I did not need to adjust my aim, merely put the crosshairs a little behind the front shoulder and squeeze. There was an orange flash in the scope and I was gratified to see the buck drop instantly. I could not have asked for a cleaner, faster dispatch.

I think I got a high-five. I don't remember.

We restrained ourselves and walked down to where the buck lay, quite dead. It was only then that I started shaking; adrenaline, you know.

We began to field-dress the buck. This is the process of removing the organs from the animal's thoracic and abdominal cavity to prevent the internal flora from spoiling the meat. Field dressing is one of those things which can only be learned by doing. My guide left me to hack up through the ribcage with a rather dull knife, while he went to get the truck. I was challenged to wrangle 170-180 pounds of dead weight while cutting through bone and flesh. The animal was very warm to the touch, and my hands were cold, so I did not mind.

Now consider the difficulties here. We had the modern conveniences of a truck to carry the game, and convenience-store ice to stuff in the cavity to keep it chilled. Yet even between the two of us it was amazingly difficult to manhandle the buck into the truck-bed. Without these things, the only option is to drag or carry the carcass to a place where it can be safely processed. In a more savage environment, like a good D&D setting, a hunter would have to stay wary of scavengers and predators which might try to steal the game. These are challenges which a wily DM might consider.

Another interesting detail: the bullet's entrance was clear, perhaps a little above the heart. My guide and I noticed another wound on the buck's opposite side, on the abdomen, near the crease of the back thigh. It was about 3 inches across, crusted and calloused over in rough way; closed, but not neatly. My guide said this was the exit wound, and I didn't argue. He was the one with the experience. Later on, when preparing the ribs to cook, I noticed a ragged hole torn through the opposite rib, which was clearly an exit wound (Exit wounds tend to be larger and more ragged than entry wounds.) That meant that the abdominal wound was

old. The antlers also bore chips and signs of hard use. These served as reminders that this was a wild animal, and had lived a dangerous and occasionally violent life. Another thing for a DM to remember: even a randomly encountered animal can have a history.

We managed to roll this buck out of the truck-bed and tuck it into the trunk of my mustang. When I backed up to our local butcher's and produced a big-game-animal from the boot, the effect was like a bizarre hat-trick. A few days later, I picked up the remains of my animal, and received

83 pounds of meat. That's both of my dogs in meat. It's probably more than a party of adventurers can eat in a

few days. Without refrigeration, they might want to can or jerk the meat, which is also a time-consuming process.

Hopefully, this story can add a little perspective for outdoorsy characters and wilderness adventures. I hope it can also offer some practical advice to other people with ambitions to hunt.

Of course, this is only scratching the surface of the topic

.jpg)